Bodoni–the Anatomy of a Type, Part II

The 45 years which Giambattista Bodoni spent as director of the Stamperia Reale at Parma established him as one of the great printers of any era. He had every opportunity to live up to his statement, “Beauty is founded on harmony, subordinate to the critique of reason.”

The Duke of Parma, Bodoni’s patron, had reason to congratulate himself on the founding of a royal press and on the selection of its director, who brought world-wide fame to Parma. After 1790 the Duke allowed his printer to accept commissions to print from outside in Italy, presenting Bodoni with the opportunity to print in other languages, such as German, English, French, and Russian.

Economy Not a Problem

The measure of Bodoni’s independence from the normal economic strictures of a practical printer may be observed from the anecdote told by the French writer, Stendahl, who visited Parma and who was enchanted with Bodoni’s printing. Upon being asked by the printer to tell him which of several French books he preferred, the writer stated that they all seem equally beautiful.

“Ah, Monsieur,” said Bodoni, “you don’t see the title of the Boileau?” Stendahl admitted that he could see nothing more perfect in that particular title, and the printer cried out, “Ah, Monsieur! Boileau Despreux in one single line of capitals! I spent six months before I could decide upon exactly that type.”

Bodoni did indeed go to great lengths with his typography, sometimes cutting several variations of one size in order to fit the copy of the title page. An inventory of this output, made in 1840, showed 25,735 punches, and 50,994 matrices, an incredible total for one man considering the fact that it took upwards of three hours to engrave the steel punch. Unquestionably Bodoni received some assistance in this monumental undertaking, although he frequently was angered when his capacity for industry was doubted.

It may be noted that while Bodoni’s reputation as a printer is secure, his standing as a scholarly printer is sometimes questioned. This is primarily the result of careless proofreading, but during his lifetime he was criticized, quite logically, upon this point.

Bodoni Widely Copied

The Bodoni types were widely copied during the early years of the 19th century, but most of the copies or less inspired and were more rigidly mechanical than the originals. The Bodoni serif in the capital letters was of the same weight as the thin stroke, but it was joined with a very slight filet, or bracket. In the lowercase letters the serif was slightly concave. In the contemporary Didot types in France these characteristics were changed to unbracketed straight-edged serifs.

Another type of this period which was imitative of the Bodoni letter was the German Walbaum type, which a recent writer has called “one of the most important vehicles of typographic expression in the German language during the 19th century.” Also, the English type design in 1791 by William Martin for the Shakespeare Press of William Bulmer has definite Bodoni characteristics, although maintaining some of the warmth of the traditional style.

Following Bodoni’s death in 1813, his widow continued the printing office, producing the great specimen book, Manuale Tipografico in 1818. She was more interested, however, in the disposal of punches and matrices than in the ordinary production of the press. In 1842 these were sold and placed in the Biblioteca Palatina in Parma. The library was bombed in 1944, but fortunately the matrices and punches had been removed to a monastery south of the city.

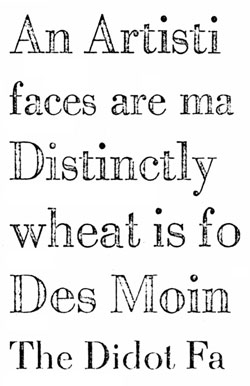

variations of Bodoni (top to bottom): Monotype, Intertype, American Type Founders, Ludlow, Bauer, Deberny & Peignot

Revival in Twentieth Century

After 1900 interest in the Bodoni types revived with a cutting issued by the Italian foundry Nebiolo in 1901. Probably the most important revival was that of Morris Benton for American Type Founders in 1911. Henry Lewis Bullen wrote that Benton received guidance from Italian sources in his recutting. It is obvious, however, that he did not attempt a close copy of the original Bodoni type, for his version is closer in spirit to the Didot letters. This is particularly noticeable in the unbracketed serifs.

The Benton cutting did inspire a number of other versions from the Linotype, Monotype, and Intertype firms. The European countries also produced copies, but they, too, were inclined to freely adapt the Bodoni idea of high contrast without following through on the details of serif structure.

In 1923 Dr. Hans Mardersteig established the Officina Bodoni in Switzerland and received permission from the Italian authorities to recast some of the original Bodoni matrices. In 1927 the office was moved to Verona, Italy, where it is still producing printing in the spirit of Bodoni himself. Martersteig’s use of the original type was instrumental in awakening interest in the Parma master printer, with the result that several new cuttings of Bodoni were made. Of these the version made available by the Bauer Type Boundary of Frankfurt seems to come closest to the spirit of the original itself.

The standard series of weights in Bodoni include the variance book, regular, and bold. Only one supplier (Bauer), however, has ventured into an extra-bold version, a surprising fact, since the type lends itself better than most styles to changes in weight. There are a number of other types which trade on the Bodoni name, such as Ultra Bodoni, Poster Bodoni, etc., but which bear no relation whatsoever to the original other than having a strong contrast of thick and thin strokes.

Strong in Text and Display

It is difficult to see how advertisers and commercial printers could get along without Bodoni. It has been used for the greatest volume of display typography of any type other than sans serif. As a book type is faring quite well. Using the Fifty Books of the Year Exhibition as an index, from 1923 through 1967, Bodoni has been selected for 108 books, ranking seventh in popularity. It has been absent from the list only six times.

While Giambattista Bodoni would not, perhaps, willingly claim fatherhood of the numerous types which presently bear his name, he can find no fault in being a household name in the printer’s craft 155 years after his death.

This article first appeared in the “Typographically Speaking” column of the August 1968 issue of Printing Impressions.